Pimoa Cthulhu

Collaborators

Marianne Hoffmeister

This is Jackalope

Typology

Residency

Year

2020

Pimoa Cthulhu: First Tentacular Writing Residency of the Institute of Postnatal Studies in collaboration with This is Jackalope

The first open call for the Pimoa Cthulhu residency, aimed at thinkers, researchers, writers and artists. Marianne Hoffmeister was his first artist in residency.

The Tentacular Writing residency is based on the idea of tentacular frameworks, of imaginaries that connect and relate the different inhabitants of this or other worlds and their environments. Through the resource of writing new images of desirable worlds can be projected, attending to, cultivating and caring for the relationships between their agents, both human and non-human, and their ecosystems. We invite to create a written work of indefinite length and open genre with which to generate narratives on the margins and from which to imagine new ways of understanding (post)nature and our place in it.

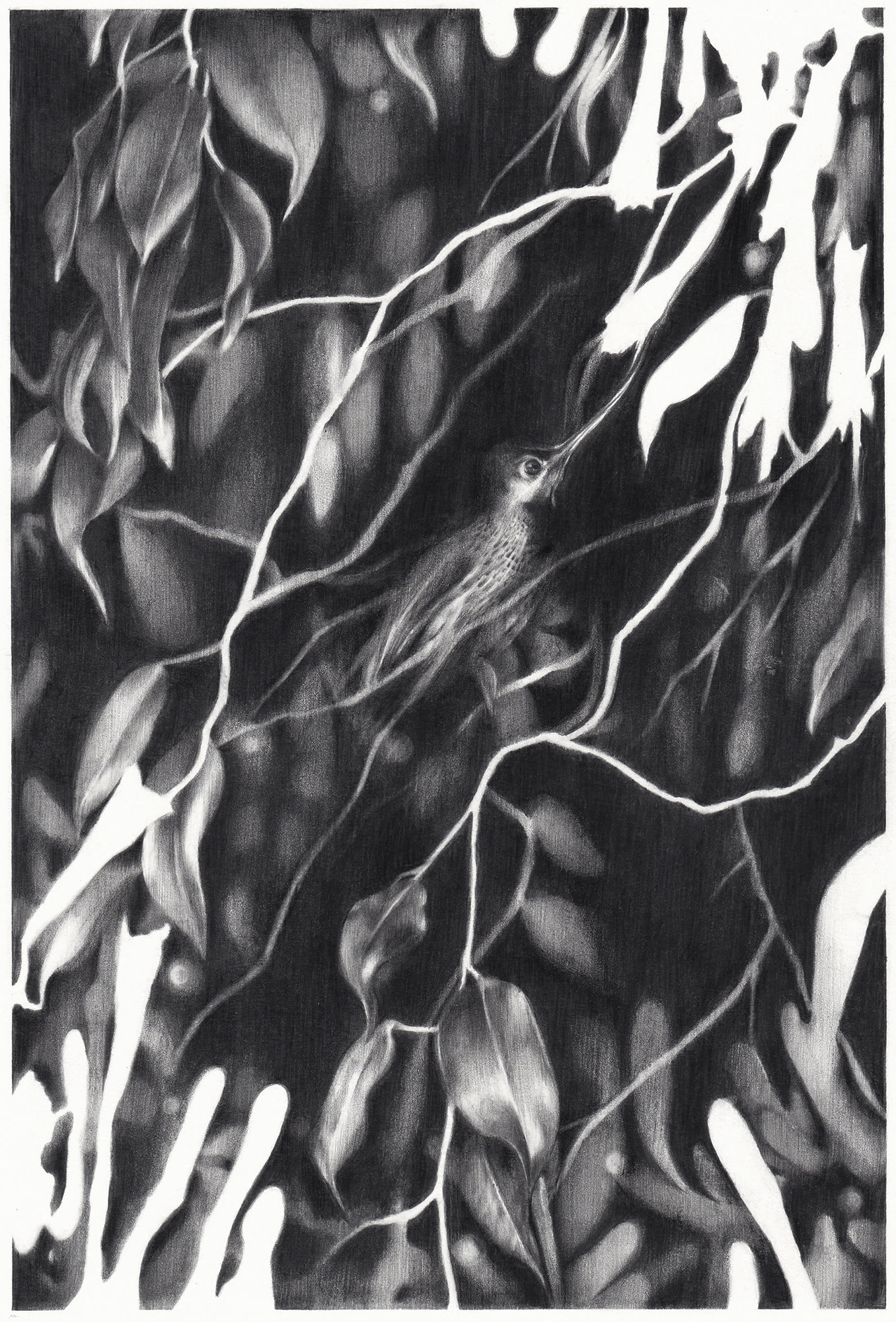

Marianne Hoffmeister was the selected artist in residency, who developed her project “Ghostly Ecology”. Her writings and drawing were published in This is Jackalope #3 publication.

Interview

We sat down with Marianne Hoffmeister at the end of the Pimoa Cthulhu Residency so she could share with us her tentacular writing ways and talk about her project.

IPS: Most people reading this don’t know about the piece that will be soon published on This is Jackalope as a result of the residency. Could you tell us in a concise way what it entails?

MH: My project is called Ghostly Ecologies which is a speculative and narrative framework rooted on the concept of the phantasmatic -ghostliness or spectrality- to suggest that there are other ways of being that dwell on the limits of understanding, outside the limits of our own subjectivity. For me, spectrality operates as a metaphorical tool to embrace a world that is made of oblique perceptions, disorientations and hiddenness. I try to think of this framework as a poetic strategy -a passage- to honor the diverse entities that have diverse ways of existing in this world and that are essential as they give shape to our existence. I'm interested in creating stories that keep us thinking about the symbiotic and intimate relationships between the invisibilities and visibilities of the world. Also, it is important to clarify that these Ghostly Ecologies are not stories of ghosts that come to haunt us from an anthropomorphic underworld: I'm not interested in addressing dystopian worlds or stories of “ecoterror”, or this kind of self-indulgent narratives about the end of the world as these renderings implicitly put our actions at the center of the world. And again, these narratives continue to have a human shape. I want to resist that. I’d rather propose an imaginarium where diverse nonhuman entities or invisibilities are the agencies that keep the world alive and connected. All these beings are world containers, world holders and world makers: they are and have always been. Therefore, I prefer to build narratives that help us reorient our attention to these ideas. The assemblage of this world is ghostly and filled with such an unknowable density that I believe that it is important to create stories that open our senses to the deep intimacies of the world, narratives that act more like constellations of diverse entangled worlds where agencies shift and slip into another. I consider Ghostly Ecology as a thought experiment that might make us reconsider our place in a world of complexities even if it remains in a domain of pure speculation.

IPS: How would you define tentacular writing after the residency?

MH: For me tentacular writing is a strategy to create stories that enact the complexities of the world, that manifest that there are so many ways of existing on this planet. Many-tentacled narratives are able to join different realms and domains that seem disparate to make them work together in rich intricacies. It is also an act of resistance to the ideas of linearity -either spatial or temporal-, binaries, and hierarchy defying the narratives about human subjects enclosed in their monolithic castles of thought. Tentacular thinking reminds us the world is made of curious and strange entanglements, that the world is formed by so many diverse beings which are also centers of their own worlds. For me, tentacular writing is a way to build bridges to a world of unexpected encounters. It offers different ways of accessing the world, which I believe is much needed now.

IPS: How has the Postnature and Contemporary Creation seminar inspired or influenced not only your writing, but you as an artist, as a thinker, as a poet?

MH: I found a community that shares similar concerns. The seminar nourished a space where I could really discuss my ideas and perspectives in the discussions generated by the group. These conversations were really insightful, I learned so much from everyone! I was also able to critically look further into the Anthropocene. I feel I am able to articulate much better on the subject. I also enjoyed very much the virtual tour of the Botanical Garden. It was very insightful to understand the botanical garden as a political space of conflict, a place of manicured order, of vegetal colonies, of the symbolic colonization of landscapes and nature: it's a materialization of ideological structures in the shape of a garden. This critical gaze was very meaningful, it is true that gardens are not naive displays but arrangements for our desires for control and possession. Some other highlights were the conference by Samaneh Moafi from Forensic Architecture and Nature is Healing by Toni Navarro and Catia Faria and just the overall tentacular approach to learning. One image that stuck with me -among so many- was of the Trinitite, this mineral created out of nuclear explosions. This image encapsulates everything the seminar is about as it turns itself into this hyperobject of what our imprint has really been. I believe the seminar helped me to have a greater sense of what a postnatural world is like and also have a deeper critical eye on many related issues such as ecofeminism, posthumanism, and other areas of study.

IPS: Now that you mention it, Trinitite is kind of a ghostly mineral.

MH: This mineral exists on this world now, it has a physical presence but it feels like a ghost of the human imprint on the world. I feel it lingers in a very strange way, it has a strange -a terrifying- aftertaste. It is like some kind of remnant, a memento, that inhabits our material present. I am just speculating but I feel the Trinitite is like a living specter, a contemporary fossil. I feel its existence warps time somehow.

IPS: How do you relate ghostly ecologies to your interest in pollination?

MH: Pollination is the perfect metaphor or example of a rich and sensuous net of interspecies mutualism and intimate co-dependency in which floral and pollinator bodies evolve as mirrors of each other, as if they were merging into one another, as inseparable flesh. For me this relationship is extremely beautiful, profound, and a perfect example of Ghostly Ecologies. That is why I chose Pollination to start building narratives for this particular framework. The agencies between pollinator and flower shift and change. It is a network of many invisible threads and also where identities shift (at least for me on a poetical level): the distinction between petal and feather becomes fuzzy. Also Pollination allows me to make studies of scale and curiosity which makes sense with my framework.

IPS: This idea of the symmetry between the feeder and the fed for me relates to the symmetry between life and death. When we chose your project, the idea of tentacular writing as a way to explore spirituality was very appealing to the Institute and This is Jackalope. We felt that postmortem tentacular writing would add an interesting perspective into subjects that are at times still taboo in occidental society and culture. I think it's quite beautiful the correlation between the physical symmetry and the spectrum symmetry you are investigating.

MH: For me this idea helps me recognize in a visual and bodily way that the assemblage of the world is ghostly or phantasmatic because it points out at the complexity and the diverse ways of existing that are threaded into it. In this sense I do not only mean living entities, but non-living, long-gone, soon-to-be born and also maybe, never-to be born beings. This sort of flux between life and death interests me. In the case of pollination, it entails a vast net of nourishment, communication and reproduction in which some foreign bodies need other beings to help them reproduce and spread. It is queer and so complex; and it is, indeed, what keeps every being of this world alive. Pollination is truly a flux of life and death. This also raises so many questions: How do flowers know which shape to take through their evolving selves? What are the physical cues that the pollinators or floral body desires? There's a myriad of pollinators that shape their bodies so they can feed on some specific flowers. Some flowers display specialized features to attract a selected set of pollinators or sometimes, just one. On a poetic level I ask: Do flowers and pollinators keep their memories even if one of them is gone forever? Can pollination continue on a ghostly realm? But most importantly, I wonder: do we share that kind of intimacy with other beings? The intimacy that vegetal bodies and pollinators share is so deep it makes me question if we, humans, have the capability of such profound intimacy.

IPS: We may never be able to feel as a bird or as a bee, but we can definitely try, and in this attempt we can actually create a deeper connection or intimacy with these other beings, opening our imagination and emotional response to other ways of living, of existing, of dying, other ways of being a ghost. I've been lucky enough to see some of the results. And I'm really excited that everyone will soon get to read what you've been working on. Thank you so much for sharing this time with us. Congratulations on the beautiful literature.

MH: Thank you.

You can find more info about the collaborators here: